French & American Children's Fiction: Comparing Cultural Clues

As my children grow towards school-age, we're reading a larger variety of short stories in French and English, and I'm delighting in the subtle differences along the way. Fiction stories are culture capsules--they rarely reveal culture overtly, but the more one reads, the more one sees how the stories reflect cultural tendencies. At the risk of wading into stereotypes, I'll share the key differences I've noticed:

Plot: French children's fiction tends to include multiple plot developments, taking the reader through a sequence of experiences without necessarily returning to the original starting point. In contrast, American fiction stories tend to have somewhat more simplified plots, with a definite arc back to the starting point so that the story seems to come full circle.

- French story example: Dans la pousette de Lisette follows Lisette in her outdoor playtime after a rainstorm passes. She meets a snail and invites him home to play, but due to his slowness she retrieves her doll carriage to carry him. Along the way they meet an elephant who wants to join in on the carriage ride but is limited by his size. He borrows his sister's carriage and they have a grand time rolling along until his sister takes it away. As the rain restarts, Lisette and the snail continue on to her house where they compare baby dolls. (Author Catharina Valckx is Dutch but grew up in France.)

- American story example: In Where the Wild Things Are, Max is sent to his room for misbehaving and finds himself in the midst of an imagined land where he reigns over monsters until the aroma of dinner brings him back to his bedroom. Even though he has journeyed for nearly an (imaginary) year, his delivered dinner is still hot.

Character: American characters are often described upfront as having certain personality traits and tendencies, whereas French characters are typically introduced by speech or actions, and their character is left to the reader to determine over the course of the story.

- French examples: Martine, a little girl (from a series of books launched in the 1950s) who often helps her mother with various tasks; Emilie (from the series by Domitille de Pressensé) who wears distinctive red slippers and prefers playing to taking a bath.

- American examples: Curious George, "a good little monkey and always very curious"; Olivia the pig who is "good at lots of things" and "is very good at wearing people out."

Endings: Story endings are likely the most telling revelations of cultural preferences. We Americans love our "happy end"--a term the French have borrowed to describe our highly preferred story finish (especially pronounced in films). Our stories most often wrap up cheerfully, idealistically, and neatly, shining with the optimism that pervades our culture. This is not to say that French children's stories are dark and sad, but they do hint at struggles that cannot be resolved neatly. If a character cannot overcome certain plot developments, well, c'est la vie. At least the story provides humor and adventure along the way.

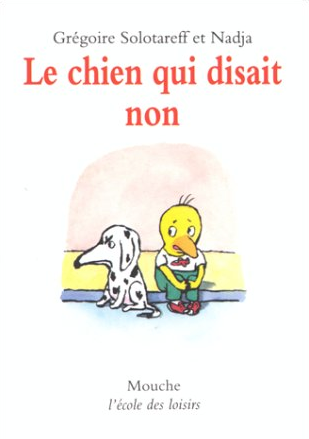

French example: In Le chien qui disait non, little Benjamin can't convince his parents to believe that his dog can speak and he's banished to his bedroom, but at least the dog finally says something other than 'no.'

American example: In Harry by the Sea, Harry the dog loses his family on a crowded beach, but he gets a free hamburger while searching for them and his family later buys a new beach umbrella so that he won't ever lose them on the beach again.

What cultural observations have you noticed in children's books? Which approaches or messages do you prefer in the stories you read your children?

This post is the last of five in a series on storytelling. It includes Amazon links for your convenience. Previous posts included:

- Getting My Children to Tell Stories in Their Minority Language

- Improving your Family Storytelling: Tips and New Approaches

- The Art of Storytelling: Orality for Parents and Children

The next blog series here at Intentional Mama will focus on aspects of French parenting. I look forward to having you join me here!